Interviewer: Olivier Burton

Does your desire to write for the theatre come from your experiences / from any specific experience as a theatre-goer / spectator?

My desire to write for the theatre comes mainly from my, albeit relatively limited, experience as an actor; my desire to be an actor came from my enjoyment of theatre as an audience member, and also from my enjoyment of theatre as literature (I have always enjoyed reading plays). I wanted to become an actor in order to be more completely engaged with theatre, to be less passive. My first exposure to theatre excited me both intellectually and emotionally. I was drawn to the energy and rigor of theatre, to the fact that it was ‘alive’ and required the active, focused participation of both those who created it and those who witnessed it. I was drawn to this particularly dynamic relationship; perhaps also to the dangers and the risks it involved.

Do you have the audience in mind when you write? And if so, how?

I write my plays line by line, attempting to create the reality of my characters and the situation they are in. I think of nothing else. An audience seems a too distant and too abstract idea to consider while I am writing. And of course, audiences vary so much, from night to night in the same theatre, from city to city, from country to country. But I do have a certain and quite conscious sense of the audience: I know that the lines I am writing will be spoken / acted out on a stage, and that this event will be witnessed by an audience. I want that audience to be interested in what is happening on stage; I don’t want to bore them. How can I avoid that? By trying to create characters and situations that are emotionally truthful; and I do this as much for myself as for any imagined audience, because the central responsibility that I feel towards my work consists of this attempt to be at least truthful. The audience is free to accept or reject the outcome of this work.

Do you write for the audience or for a particular audience (knowing that a theatre audience can be quite reduced in number and quite specific)?

As I’ve said above, if I write for an audience at all, it is for the audience, which is quite an abstract concept. I suppose that, ultimately, I am the audience. I am certainly the first audience member to be exposed to my work.

What would the ideal audience be?

People who come to the theatre because they are interested in the theatre, in its possibilities and perhaps even in its failures; who come to the theatre because they understand that a night at the theatre is more than simply understanding the content of a play, but an event that allows a particular emotional and intellectual fraternity; who understand that they are witnessing the creation of a work of art that exists only in the moment that they witness it; who understand this kind of fragility and this kind of strength.

I should say that I have sat among audiences like this and felt . . . the thrill of such company.

Do you usually / often attend the performances of your work? [Do you often see your work performed on stage?]

I do, as much as I can. Does a composer want to hear their music performed by musicians? Or would they be satisfied never hearing the music they have written?

Can you describe a good experience you had as a member of the audience / a nice memory as a spectator?

I have been an audience member at performances that I will never forget, that have become an important part of my life. It’s too difficult to single out any one experience; but I should mention that I have seen plays of my own that have had a deep effect on me, certainly not because they were my plays, but because in performance they became something other than what I had imagined and written; through the work of the actors, the director and the designers, the plays had taken on another life, a life independent of me. I was able to watch them without any preconceptions: the plays had escaped the grasp of my imagination and had become entities in their own right. I stood outside them and experienced them perhaps in a way that a stranger to them might have. For me, this was a wonderful experience.

Can you describe a bad experience you had as a member of the audience / a bad memory as a spectator?

I have had quite a few, especially in Australia. I remember being at one play (which shall remain nameless, as will its author) where the boredom that I felt was like a physical force emanating from the stage, pushing me back into my seat, crushing me…and that was after only twenty minutes. When the play entered its second hour I felt as if I was about to scream. I left the theatre trembling with rage and exhaustion. There is almost no experience as bad as a tedious night at the theatre, because it can make you feel as if your life is draining away, moment by moment. There are certain types of plays that always do this to me: plays that set out to ‘teach’ the audience something, or to ‘answer ‘certain questions, or to ‘expose’ or ‘define’ certain cultural or political or sexual or intellectual ‘truths’; plays, in other words, whose content might be better left to second-rate journalists or talk-back radio hosts . . . but that always seem to last for hours and hours and hours . . . .

Do the audience’s reactions/response to a play influence your work when you set to write the next play?

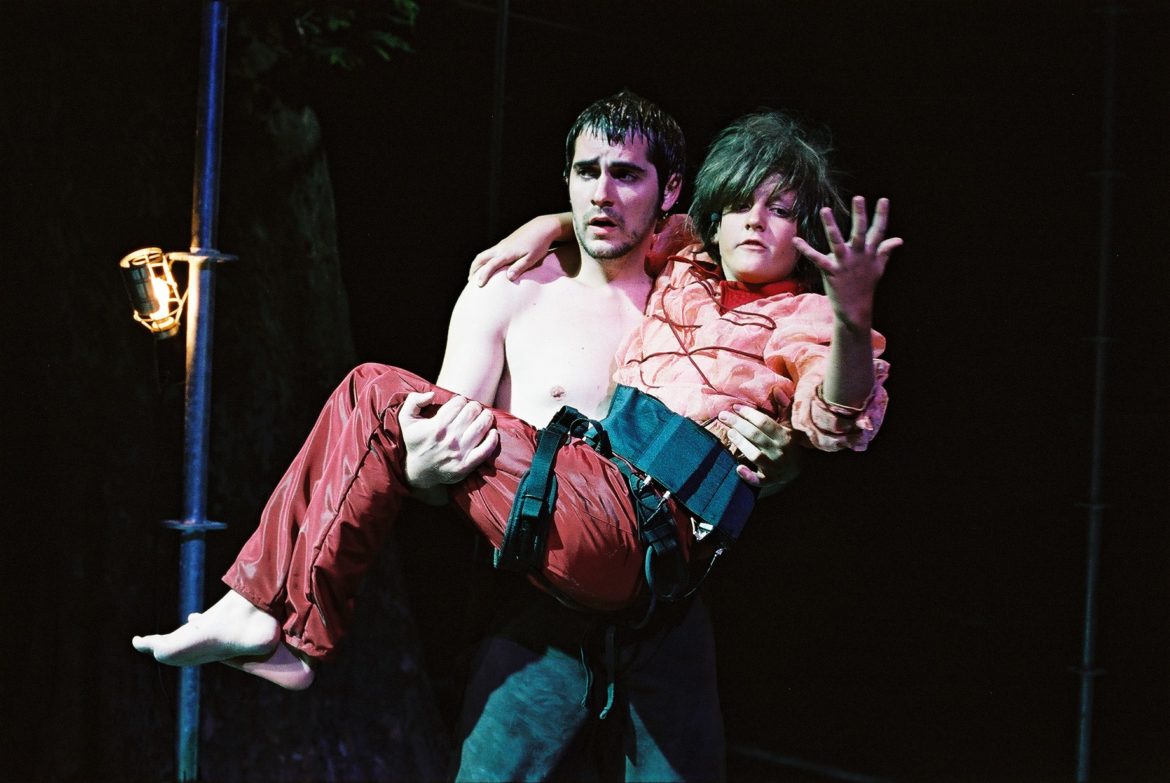

THE EARTH THEIR MANSION is a play about the disintegration of a family of farmers: the son is leaving home, turning his back on his inheritance; the farm is being sold to real estate developers; the relationship between the son and his parents is troubled and unresolved. The play is very much about the decline not only of a rural economy, but a rural morality or ethic and the difficulty (perhaps even the tragedy) of change.

I was at a performance of the play in Douai. It was a very austere and very beautiful production, directed by Jacques Descorde. I was approached after the performance by a man who told me that he was a farmer. He said that I had ‘understood everything’. He seemed a very stern and proud man, but his comment was full of feeling and spoken despite his obvious shyness. I was taken aback by what he had said, certainly moved by it, and flattered I suppose. I didn’t quite know how to respond. As I remember, I said ‘Thank you’.

I had presumed to write a play about a world I knew very little of: I am not a farmer, my family are not / have never been farmers, I know nothing about farming from any first hand experience (despite the cultural clichés that abound about Australians, I am, in fact, a completely urban creature). But I had imagined (presumed) that the dislocations and emotional ruptures that I portrayed in THE EARTH THEIR MANSION would be true of any family, rural or urban. What I had ‘invented’ was how these things might be echoed in that family’s relationship to their land, to the earth they stood upon and earned their living by. I simply treated the land itself as another character; a character I had invented, as I had invented the father, the mother and their son.

I had imagined, in the urban confines of my room, in the middle of my urban life that if my son turned his back on me, my heart would break; if all that I had made of my life was considered of no consequence or value, if in the eyes of the world all that I valued was suddenly worthless, my life would seem meaningless. These things were true for me, and for that farmer. Our brief encounter was , for me, a confirmation that I has succeeded in discovering a place where the audience and I could meet; a common ground that we shared. That fact gave me confidence and increased my desire to write for the theatre.

Do the following principles guide your work?

“To please while educating / To please and educate at the same time?”

Intelligibility

Provocation

Could you think of other principles guiding your work?

It isn’t my job to educate anyone, and I would never presume to do so. What would I teach them…how to write plays? To think as I do?

Who should I seek to please? How can I know what would please them? Should I teach them what pleases me? And yet to please is at the heart of theatre; to delight and engage the audience, perhaps to move them. But these things cannot be my guiding principles, they can only remain the possible outcomes / effects of my work.

Certainly, I would like my plays to be intelligible. But only one member of the audience need understand what I am saying; that would be enough.

Who would I provoke? Why should I wish to provoke them? To what end? In the hope of what outcome?

I am guided by the fact that I have decided to tell stories and the hope that there are some people who will decide to listen to them.

If my hope is fulfilled, I may please, I may perhaps educate and provoke those I have never met in ways that I cannot know.

The audience’s sanction: Is the audience always right? Is unanimity important for you?

No. Yes. Maybe. Sometimes.

As Mister Brecht (reportedly) once said: If everyone likes a play, there’s obviously something wrong with it!

Published in Les Petits Cahiers de la Commune Volume 14

Theatre de la Commune, Paris, 2006